Per Christensen, Colleen Sims and Bruce G. Ward

Key words. Ecological restoration, pest fauna control, captive breeding, foxes, cats.

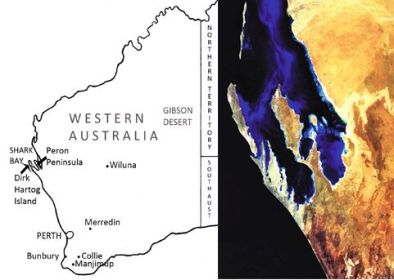

Figure 1. The Peron Peninsula divides the two major bays of the Shark Bay World Heritage Area, Western Australia.

Introduction. In 1801, 23 species of native mammals were present in what is now Francois Peron National Park. By 1990 fewer than half that number remained (Fig 1.). Predation by introduced foxes and cats, habitat destruction by stock and rabbits had driven many native animals to local extinction.

Project Eden was a bold conservation project launched by the WA government’s Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM -now Dept of Parks and Wildlife) that aimed to reverse extinction and ecological destruction in the Shark Bay World Heritage Area.

The site and program. Works commenced in Peron Peninsula – an approx. 80 km long and 20 km wide peninsula on the semi-arid mid-west coast of Western Australia (25° 50′S 113°33′E) (Fig 1). In the early 1990s, removal of pest animals commenced with the removal of sheep, cattle and goats and continued with the control of feral predators. A fence was erected across the 3km ‘bottleneck’ at the bottom of the peninsula where it joins the rest of Australia (Fig 2) to create an area where pest predators were reduced to very low numbers.

Figure 2. The feral proof fence was erected at the narrow point where Peron Peninsula joins the mainland.

Once European Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) (estimated at 2500 animals) was controlled and feral Cat (Felis catus) reduced to about 1 cat per 100 km of monitored track, sequential reintroductions of five locally extinct native animals were undertaken (Figs 3 and 4). These included: Woylie (Bettongia penicillata – first introduced in 1997), Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata – 1997), Bilby (Macrotis lagotis – 2000), Rufous Hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes hirsutus – 2001), Banded Hare-wallaby (Lagostrophus fasciatus -2001), Southern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus – 2006) and Chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroi geoffroi -2011?)

Methods. Cat baiting involved Eradicat® cat baits, which were applied annually during March–April at a density of 10 to 50 baits/km2. Cat baiting continued for over 10 years, supplemented with a trapping program, carried out year round over a 8 -year period. Cat trapping involved rolling 10 day sessions of leghold trapping along all track systems within the area, using Victor Softcatch No. 3 traps and a variety of lures (predominantly olfactory and auditory).Tens of thousands of trap nights resulted in the trapping of up to 3456 animals. Fox baiting involved dispersal of dried meat baits containing 1080 poison by hand or dropped from aircraft across the whole peninsula. Baiting of the peninsula continues to occur annually, and removes any new foxes that may migrate into the protected area and is likely to regularly impact young inexperienced cats in the population, with occasional significant reductions in the mature cat population when environmental conditions are favourable.

Malleefowl were raised at the Peron Captive Breeding Centre from eggs collected from active mounds in the midwest of Western Australia. Woylies were reintroduced from animals caught in the wild from sites in the southwest of Western Australia, with Bilbies sourced from the Peron Captive Breeding Centre, established by CALM in 1996 to provide sufficient animals for the reintroductions. The centre has since bred more than 300 animals from five species

Monitoring for native mammals involved radio-tracking of Bilbies, Woylies, Banded Hare Wallabies, Rufous Hare-Wallabies, Southern Brown Bandicoots, Chuditch and Malleefowl at release, cage trapping with medium Sheffield cage traps and medium Eliots, as well as pitfall trapping of small mammals. The survey method for cats utilized a passive track count survey technique along an 80 km transect through the long axis of the peninsula. The gut contents of all trapped cats were examined.

Figure 3. Once foxes were controlled and cats reduced to about 1 cat per 100 km of monitored track, sequential reintroductions of five locally extinct native animals were undertaken. Woylies were first introduced in 1997 from animals caught in the wild at sites in southwest Western Australia.

Figure 4. Tail tag being fitted to a Bilby. (Bilbies were re-introduced to the Peron Peninsula in 2000, from animals bred in the Peron Captive Breeding Centre.)

Results. Monitoring has shown that two of the reintroduced species – the Malleefowl and Bilby – have now been successfully established. These species are still quite rare but they have been breeding on the peninsula for several years The Woylie population may still be present in very low numbers, but despite initial success and recruitment for six or seven years, has gradually declined due to prolonged drought and low level predation on a small population. Although the released Rufous Hare-wallabies and the Banded Hare-wallabies survived for 10 months and were surviving and breeding well, they disappeared because of a high susceptibility to cat predation and other natural predators like wedge-tailed eagles. Although some predation of Southern Brown Bandicoot has occurred and the reintroduction is still in the early stages, this species has been breeding and persisting and it is hoped that they will establish themselves in the thicker scrub of the peninsula.

Lessons learned. We found that the susceptibility to predation by cats and foxes varies considerably between species. Malleefowl are very susceptible to fox predation because the foxes will find their mound nests, dig up their eggs up and eat them – consequently wiping them out over a period of time. As cats can’t dig, Malleefowl can actually exist with a fairly high level of cats. Bilbies live in their burrows and are very alert so they can persist despite a certain level of cats. But the Rufous Hare-wallaby and the Banded Hare-wallaby are very susceptible to cat predation and fox predation due to their size and habits.

Examination of the period of time when species disappeared from the Australian mainland showed that there was a sequence of extirpations, reflecting the degree to which the species were vulnerable to pest predators. The ones that survived longest are those that are less vulnerable. This suggests that if complete control of predators is not possible (considering cat control is extremely difficult), it is preferable to focus on those animals that are least vulnerable. While it could be argued that reintroductions should be delayed until such time as all the cats and foxes have been removed, such a delay (which might take us 10, 20 or even 100 years) is likely to exceed the period of time many of these species will survive without some sort of assistance. It is likely to be preferable to proceed with reintroductions although we might be losing some animals.

Future directions. As with the majority of mainland reintroduction projects, level of predator control is the key to successful establishment of reintroduced fauna. The Project is currently under a maintenance strategy and future releases, which included the Western Barred Bandicoot (Perameles bougainville), Shark Bay Mouse (Pseudomys fieldi), geoffroi), Greater Stick-nest Rat (Leporillus conditor) and Red-tailed Phascogale (Phascogale calura) are on hold until improved cat control techniques are available. Despite the uncertain future for reintroductions of these smaller species, ongoing feral animal control activities and previous reintroductions have resulted in improved conditions and recovery for remnant small native vertebrates (including thick billed grass wrens, woma pythons and native mice), and new populations of several of the area’s threatened species which are once again flourishing in their original habitats.

Acknowledgements: the program was carried out by Western Australia’s Department of Parks and Wildlife and we thank the many Departmental employees, including District and Regional officers for their assistance over the years, and the many, many other people that have volunteered their time and been a part of the Project over the years, for which we are very grateful.

Contact: Colleen Sims, Research Scientist, Department of Parks and Wildlife (Science and Conservation Division, Wildlife Research, Wildlife Place, Woodvale, WA 6026, Australia, Tel: +61 8 94055100; Email: colleen.sims@dpaw.wa.gov.au). Also visit: http://www.sharkbay.org.au/project-eden-introduction.aspx

Further detail and other work in WA: