Nancy Pallin

[Update to EMR feature – Pallin, Nancy (2001) Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve Habitat restoration project, 15 years on. Ecological Management & Restoration 1:1, 10-20. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1442-8903.2000.00003.x]

Key words: bush regeneration, community engagement, wallaby browsing, heat events, climate change

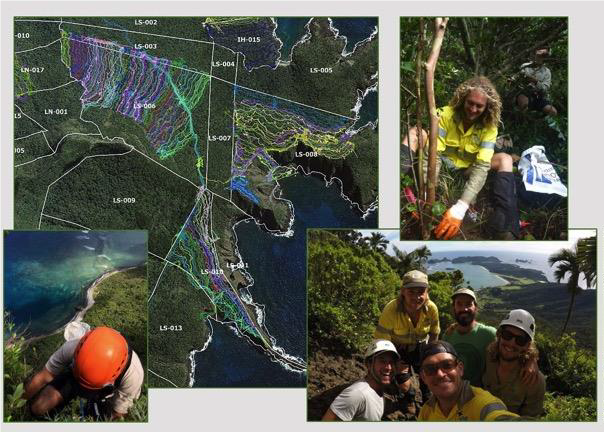

Figure 1. Habitat restoration areas at Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve within the urban area of Gordon, showing areas treated during the various phases of the project. Post-2000 works included follow up in all zones, the new acquisition area, the pile burn site, the ecological hot burn site and sites where vines have been targeted. (Map provided by Ku-ring-gai Council.)

Introduction. The aim of this habitat restoration project remains to provide self-perpetuating indigenous roosting habitat for Grey-headed Flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) located at Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve in Gordon, NSW Australia (Fig 1). The secondary aim was to retain the diversity of fauna and flora within the Flying-fox Reserve managed by Ku-ring-gai Council. Prior to works, weed vines and the activity of flying-foxes in the trees had damaged the canopy trees while dense weed beneath prevented germination and growth of replacement trees. Without intervention the forest was unable to recover. Natural regeneration was assisted by works carried out by Bushcare volunteers and Council’s contract bush regeneration team. The work involved weed removal, pile burns and planting of additional canopy trees including Sydney Bluegum (Eucalyptus saligna), which was expected to cope better with the increased nutrients brought in by flying-foxes.

Figure 2. The changing extent of the Grey-headed Flying-fox camp from the start of the project, including updates since 2000. (Data provided by KBCS and Ku-ring-gai Council)

Significant changes have occurred for flying-foxes and in the Reserve in the last 20 years.

In 2001 Grey-headed Flying-fox was added to the threatened species lists, of both NSW and Commonwealth legislation, in the Vulnerable category. Monthly monitoring of the number of flying-foxes occupying the Reserve has continued monthly since 1994 and, along with mapping of the extent of the camp, is recorded on Ku-ring-gai Council’s Geographical Information System. Quarterly population estimates contribute to the National Monitoring Program to estimate the population of Grey-headed Flying-fox. In terms of results of the monitoring, the trend in the fly-out counts at Gordon shows a slight decline. Since the extreme weather event in 2010, more camps have formed in the Sydney basin in response to declining food resources.

In 2007, prompted by Ku-ring-gai Bat Conservation Society (KBCS), the size of the Reserve was increased by 4.3 ha by NSW Government acquisition and transfer to Council of privately owned bushland. The Voluntary Conservation Agreement that had previously established over the whole reserve in 1998 was then extended to cover the new area. These conservation measures have avoided new development projecting into the valley.

From 2009 Grey-headed Flying-fox again shifted their camp northwards into a narrow gully between houses (Fig 2). This led to human-wildlife conflict over noise and smell especially during the mating season. Council responded by updating the Reserve Management Plan to increase focus on the needs of adjoining residents. Council removed and trimmed some trees which were very close to houses. In 2018 the NSW Government, through Local Governments, provided grants for home retrofitting such as double glazing, to help residents live more comfortably near flying-fox camps.

Heat stress has caused flying-fox deaths in the Reserve on five days since 2002. Deaths (358) recorded in 2013, almost all were juveniles of that year. KBCS installed a weather station (Davis Instruments Vantage Pro Plus, connected through a Davis Vantage Connect 3G system) and data loggers to provide continuous recording of temperature and humidity within the camp and along Stoney Creek. The station updates every 15 minutes and gives accurate information on conditions actually being experienced in the camp by the flying-foxes. The data is publicly available http://sydneybats.org.au/ku-ring-gai-flying-fox-reserve/weather-in-the-reserve/Following advice on the location and area of flying-fox roosting habitat and refuge areas on days of extremely high temperatures (Fig 3.) by specialist biologist Dr Peggy Eby, Council adopted the Ku-ring-gai Flying-fox Reserve 10 Year Management and Roosting Habitat Plan in 2018. Restoration efforts are now focused on improving habitat along the lower valley slopes to encourage flying-foxes to move away from residential property and to increase their resilience to heat events which are predicted to increase with climate change.

Figure 3. Map showing the general distribution of flying-foxes during heat events, as well as the location of exclosures. (Map provided by Ku-ring-gai Council)

Further works undertaken. By 2000 native ground covers and shrubs were replacing the weeds that had been removed by the regeneration teams and Bushcare volunteers. However, from 2004, browsing by the Swamp Wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) was preventing growth of young trees and shrubs. Bushcare volunteers, supported by KBCS and Council responded by building tree cages made from plastic-mesh and wooden stakes. Reinforcing-steel rods replaced wooden stakes in 2008. From 2011, the Bushcare volunteers experimented with building wallaby exclosures, to allow patches of shrubs and groundcovers to recover between trees (Figs 3 and 4). Nineteen wallaby exclosures have been built. These range in size from 7m2 to 225m2 with a total area of 846m2. Wire fencing panels (Mallee Mesh Sapling Guard 1200 x 1500mm) replaced plastic mesh in 2018. Silt fence is used on the lower 0.5m to prevent reptiles being trapped and horizontally to deter Brush Turkey (Alectura lathami) from digging under the fence.

The wallaby exclosures have also provided an opportunity to improve moisture retention at ground level to help protect the Grey-headed Flying-fox during heat events. While weed is controlled in the exclosures south of Stoney Creek, those north of the creek retain Trad and privets, consistent with the 10 Year Management and Roosting Habitat Plan.

Madeira Vine (Anredera cordifolia) remained a threat to canopy trees along Stoney Creek for some years after 2000, despite early treatments. The contract bush regen team employed sInce 2010 targeted 21 Madiera Vine incursions.

A very hot ecological burn was undertaken in 2017 by Council in order to stimulate germination of soil stored seed and regenerate the Plant Community Type (PCT) – Smooth-barked Apple-Turpentine-Blackbutt tall open forest on enriched sandstone slopes and gullies of the Sydney region (PCT 1841). This area was subsequently fenced. The contract bush regeneration team was also employed for this work to maintain and monitor the regeneration in the eco-burn area (720 hours per year for both the fire and Madiera Vine combined).

Figure 4. Exclusion fence construction method. Pictured are Bushcare volunteers, Jill Green and Pierre Vignal. (Photo N Pallin).

Figure 5. Natural regeneration in 2018 in (unburnt) exclosure S-6 (including germination of Turpentines). (Photo N. Pallin)

Further results to date. The original canopy trees in Phase 1 and Phase 2 (1987 -1997) areas have recovered and canopy gaps are now mostly closed. Circumference at breast height measurements were taken for seven planted Sydney Blue gum trees. These ranged from 710 to 1410mm with estimated canopy spread from 2 to 6m. While original Turpentine (Syncarpia glomulifera) had circumferences from 1070 and 2350mm with canopy spread estimated between 5and 8m, those planted or naturally germinated now have circumference measurements between 420 and 980mm with canopy spread estimated from 1.5 to 3m. A Red Ash (Alphitonia excelsa) which naturally germinated after initial clearing of weeds now has a circumference of 1250mm with a canopy spread of 5m. Also three Pigeonberry Ash (Elaeocarpus kirtonii) have circumference from 265 to 405mm with small canopies of 1 to 2m as they are under the canopies of large, old Turpentines. As predicted by Robin Buchanan in 1985 few Blackbutt (Eucalyptus pilularis) juveniles survived while the original large old trees have recovered and the Sydney Bluegum trees have thrived.

In the Phase 3 (1998 – 2000) area south of Stoney Creek the planted Sydney Blue Gum now have circumferences measuring between 368 and 743 (n7) with canopy spread between 2 and 6 m. in this area the original large trees have girths between 1125 and 1770mm (n7) whereas trees which either germinated naturally or were planted now range from 130 to 678mm (n12). These measurement samples show that it takes many decades for trees to reach their full size and be able to support a flying-fox camp.

Wallaby exclosures constructed since 2013 south of Stoney Creek contain both planted and regenerated species. Eight tree species, 11 midstorey species, 27 understorey species and eight vines have naturally regenerated. Turpentines grew slowly, reaching 1.5m in 4 years. Blackbutts thrived initially but have since died. In exclosures north of the creek, weeds including Large-leaved Privet, Ligustrum lucidum, Small-leaved privet, L. sinense, Lantana, Lantana camara, and Trad, Tradescantia fluminensis) have been allow to persist and develop to maximise ground moisture levels for flying-foxes during heat events. Outside the exclosures, as wallabies have grazed and browsed natives, the forest has gradually lost its lower structural layers, a difference very evident in Fig 6.

Figure 6. Visible difference in density and height of ground cover north and south of Stoney creek. (Photo P. Vignal)

Coachwood (Ceratopetalum apetalum) were densely planted in a 3 x 15m exclosure under the canopies of mature Coachwood next to Stoney Creek in 2015. In 4 years they have reached 1.5m. In this moist site native groundcovers are developing a dense, moist ground cover.

Madiera Vine, the highest-threat weed, is now largely confined to degraded edges of the reserve, where strategic consolidation is being implemented with a view to total eradication.

In the hot burn area, which was both fenced and weeded, recruitment has been outstanding. One 20 x 20m quadrat recorded 58 native species regenerating where previously 16 main weed species and only 6 native species were present above ground. A total of 20 saplings and 43 seedlings of canopy species including Eucalyptus spp., Turpentine and Coachwood were recorded in this quadrat where the treatment involved weed removal, burning and fencing (S. Brown, Ku-ring-gai Council, July 2019, unpublished data). Unfortunately, however, the timing and location of the burn did not take into account its impact on the flying-fox camp and there was some damage to existing canopy trees. It will be many years before the canopy trees, which are regenerating, will be strong enough to support flying-foxes.

Monitoring from the weather station and data loggers has shown that close to Stoney Creek on a hot day it is typically 2-3° C cooler, and 5-10% higher in humidity, than in the current camp area (pers. comm. Tim Pearson). During heat events the flying-foxes move to this cooler and moister zone, increasing their chances of survival.

Fauna observed other than flying-foxes includes a pair of Wedge-tail Eagle ( Aquila audax plus their juvenile, a nesting Grey Goshawk (Accipiter novaehollandiae) and a Pacific Baza (Aviceda subcristata). Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua) individuals continue to use the valley. The presence of raptors and owls indicate that the ecosystem processes appear to be functional. Despite the decline of the shrub layer outside fenced areas, the same range of small bird species (as seen prior to 2000) are still seen including migrants such as Rufous Fantail ( Rhipidura rufifrons) which prefers dense, shady vegetation. The first sighting of a Noisy Pitta (Pitta versicolor) was in 2014. Long-nosed Bandicoot (Perameles nasuta) individuals appear and disappear, while Swamp Wallaby remains plentiful.

Lessons learned and future directions. Climate change is an increasing threat to Pteropus species. On the advice of Dr Eby, Flying-fox Consultant, Council, KBCS and Bushcare Volunteers agreed to retain all vegetation including weeds such as Large-leaved Privet and Small-leaved Privet, patches of the shrub Ochna (Ochna serrulata) and Trad as a moist ground cover in the camp area and areas used by the flying-foxes during heat events.

Building cheap, lightweight fencing can be effective against wallaby impacts, provided it is regularly inspected and repaired after damage caused by falling branches. This style of fencing has the additional advantage of being removable and reusable. It has been proposed that, to provide understory vegetation to fuel future burns in parts of the reserve away from the flying-fox camp, further such temporary fencing could be installed.

Ku-ring-gai Council has commenced a program to install permanent monitoring points to annually record changes in the vegetation, consistent with the state-based Biodiversity Assessment Method.

Stakeholders and Funding bodies. Members of KBCS make donations, volunteer for monthly flyout counts, Bushcare and present educational events with live flying-foxes. KBCS hosts the website www.sydneybats.org.au. Ku-ring-gai Council which is responsible for the Reserve has been active in improving management to benefit both residents and flying-foxes. Ku-ring-gai Environmental Levy Grants to KBCS have contributed substantially to purchase of fencing materials and the weather station. http://www.kmc.nsw.gov.au/About_Ku-ring-gai/Land_and_surrounds/Local_wildlife/Native_species_profiles/Grey-headed_flying-fox

Thank you to Jacob Sife and Chelsea Hankin at Ku-ring-gai Council for preparing the maps and to volunteer Pierre Vignal for assistance with tree measurements, downloading data loggers and a photo. Researcher, Tim Pearson installed the weather station.

Contact information. Nancy Pallin, Management Committee member, Ku-ring-gai Bat Conservation Society Inc. PO Box 607, Gordon 2072 Tel 61 418748109. Email: pallinnancy@gmail.com