Geoff Lambert, and Judy Lambert

[Update to EMR Feature – Geoff Lambert and Judy Lambert (2015) Progress with restoration and management of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub on North Head, Sydney. Ecological Management & Restoration, 16:2, 95-199. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/emr.12160]

Key Words. Banksia Scrub, North Head, Critically Endangered Ecological Community, Diversity.

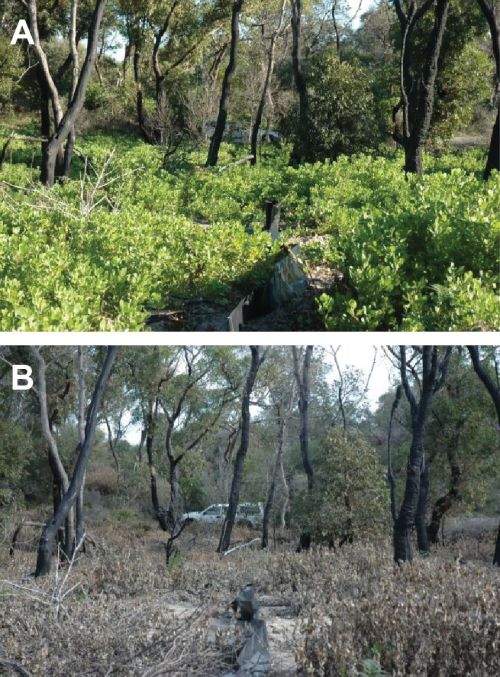

Fig 1. Images of the same location over time, taken from “walk-through” photographic surveys (top to bottom) pre-fire, immediate post-fire and 5-years post-fire. (Photos Geoff Lambert)

Introduction. In the original feature, we reported on a number of projects related to the fire ecology of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (ESBS), also known as Coastal Sand Mantle Heath (S_HL03), located in conserved areas on North Head, Sydney Australia. Following a Hazard Reduction burn in September 2012, we examined changes in species numbers and diversity and compared these measures with control areas which had been thinned. We fenced one-third of the survey quadrats to test the effects of rabbit herbivory. There had been no fire in this area since 1951.

Twelve months after treatment, burned ESBS had more native plants, greater plant cover, more native species, greater species diversity and fewer weeds than did thinned ESBS (Fig 1). Areas that had been fenced after fire had “superior” attributes to unfenced areas. The results suggested that fire could be used to rejuvenate this heath and that this method produced superior results to thinning, but with a different species mix. Results of either method would be inferior were attempts not made to control predation by rabbits (See 2015 report).

Further works undertaken. In 2015 and 2017 we repeated the surveys, including photographic surveys on the same quadrats. Further Hazard Reduction burns were conducted, which provided an opportunity to repeat the studies reported in the 2015 feature. The study design of the burns was broadly similar to the earlier study, but rabbits were excluded by fencing four large “exclosures” over half the burn site. The pre-fire botanical survey was carried out in 2014, with logistical difficulties delaying the burn until late May 2018. Drought and other factors saw a post-fire survey delayed until October 2019. Photographic surveys of the quadrats have been completed.

Seven cm-resolution, six-weekly, aerial photography of North Head is regularly flown by Nearmap© (Fig 2). We use this photography to monitor the whole of the headland and, in particular, the various burn areas. In order to extrapolate from our quadrat-based sampling (usually 1% of a burn area), the University of Sydney flew 5mm-resolution UAV-based surveys on our behalf, on one of the 2012 burn areas and on the 2018 burn area in November 2017 (Fig 3) .

Apart from the fire studies, the general program of vegetation propagation and management has been continued by the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust and the North Head Sanctuary Foundation. The Australian Wildlife Conservancy has also undertaken a “whole of headland”, quadrat-based vegetation survey as the first stage of its “Ecological Health” rolling program for its sites.

Fig 2. Nearmap© site images (top to bottom) pre-fire, immediate post-fire and 7-years post-fire. (Photos Nearmap)

Further results. The original results suggested that fire could be used advantageously to rejuvenate ESBS and produced superior results to thinning. While subsequent photographic monitoring shows distinct vegetation change (Figs 1 and 2), on-ground monitoring showed that by five years after the fire we could no longer say this with any optimism. In summary:

- In the immediate fire aftermath, there was vigorous growth of many species

- Over the ensuing 5 years, plants began to compete for space, with many dropping out

- Species diversity was high following the fire but then dropped below pre-fire levels

- Some plants (e.g. Lepidosperma and Persoonia spp.) came to dominate via vegetative spread

- The reed, Chordifex dimorphus has almost disappeared

- Tea-trees (Leptospermum spp.) are gradually making a comeback

- Between 2015 and 2017, ESBS species numbers were outpaced by non-ESBS species, but held their own in terms of ground cover.

The total disappearance of Chordifex (formerly an abundant species on North Head and prominent in the landscape) from fully-burned quadrats was not something that we could have predicted. This species is not in the Fire Response database, although some Restio spp. are known to be killed by fire. This contributes greatly to the visual changes in the landscape. The great proliferation of Lance Leaf Geebung (Persoonia lanceolata) has also changed the landscape amenity (Fig 1, bottom).

To summarise, the 2012 burn has not yet restored ESBS, but has produced a species mix which may or may not recover to a more typical ESBS assemblage with ongoing management over time. Given that the area had not been burned for 60 years, it may be decades before complete restoration.

Our further studies on the use of clearing and thinning on North Head as an alternative to fire (“Asset Protection Zone Programme”), indicates that thinning and planting can produce a vegetation community acceptable for asset protection fire management and potentially nearly as rich as unmanaged post-fire communities (Fig 4). It is necessary to actively manage these sites by removing fire-prone species every two years. In addition, a trial has been started to test whether total trimming of all except protected species to nearly ground level in an APZ, is an option for longer-term management.

Fig 3. “Thinning Experiment” fenced quadrat #3 in July 2019. The quadrat was created in 2013 by removing Coastal Teatree (Leptospermum laevigatum) and Tree Broom Heath (Monotoca elliptica). The experimental design is a test of raking and seeding, with each treatment in the longer rows. All non-endangered species plants were trimmed to 0.25 metres height in mid-2017. (Photo Geoff Lambert)

Lessons learned and future directions. It is too early to say whether we can maintain and/or restore North Head’s ESBS with a single fire. Further fires may be required. A similar conclusion has been drawn by the Centennial Parklands Trust, with its small-scale fire experiments on the York Road site. We need new and better spot- and broad-scale surveys and further burns in other areas on North Head over a longer period. The spring 2019 survey, just completed, offers an opportunity to better assess the notion that fire is beneficial and necessary.

It will be necessary to monitor the effects of future fires on ESBS diversity closely and for much longer than five years. More active management of the post-fire vegetation may be needed, as we have previously discussed in the feature, and as happens at Golf Club sites (also see video) .

The 2012 burn was relatively “cool”. There is some evidence that “hot” burns (such as have been carried out by NSW Fire and Rescue at some Eastern Suburbs golf courses) may produce improved restoration of ESBS. The 2018 burn on North Head was planned as a “hot” burn. This was not completely achieved, but we may be able to compare “hot” and “cool” burn patches within it.

Fig 4. A 2017 UAV image of quadrat 23 five years after the 2012 burn. The image has been rotated to show the quadrat aligned on the UTM grid. The red square shows the rabbit-proof fences; the black square shows the survey quadrat and the blue squares show the four 1×1 metre vegetation plots. The resolution is approximately 5 mm. (Photo University of Sydney Centre for Field Robotics)

Stakeholders. Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, North Head Sanctuary Foundation. Australian Wildlife Conservancy, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Fire & Rescue NSW.

Funding Bodies. Foundation for National Parks & Wildlife [Grant No. 11.47], Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, Australian Wildlife Conservancy.

Contact Information. Dr G.A.Lambert, Secretary, North Head Sanctuary Foundation, (P.O.Box 896, BALGOWLAH 2093, Tel: +61 02 9949 3521, +61 0437 854 025, Email: G.Lambert@iinet.net.au. Web: https://www.northheadsanctuaryfoundation.org.au/